The Shared Delusion: Both doomers and dreamers assume current technology leads to AGI. They’re both wrong

Excel didn’t kill accountants; it gave them better tools. Yet, with AI, we’ve abandoned this logic in favor of a collective fantasy. We’re treating a sophisticated calculator as a human replacement rather than a human multiplier.

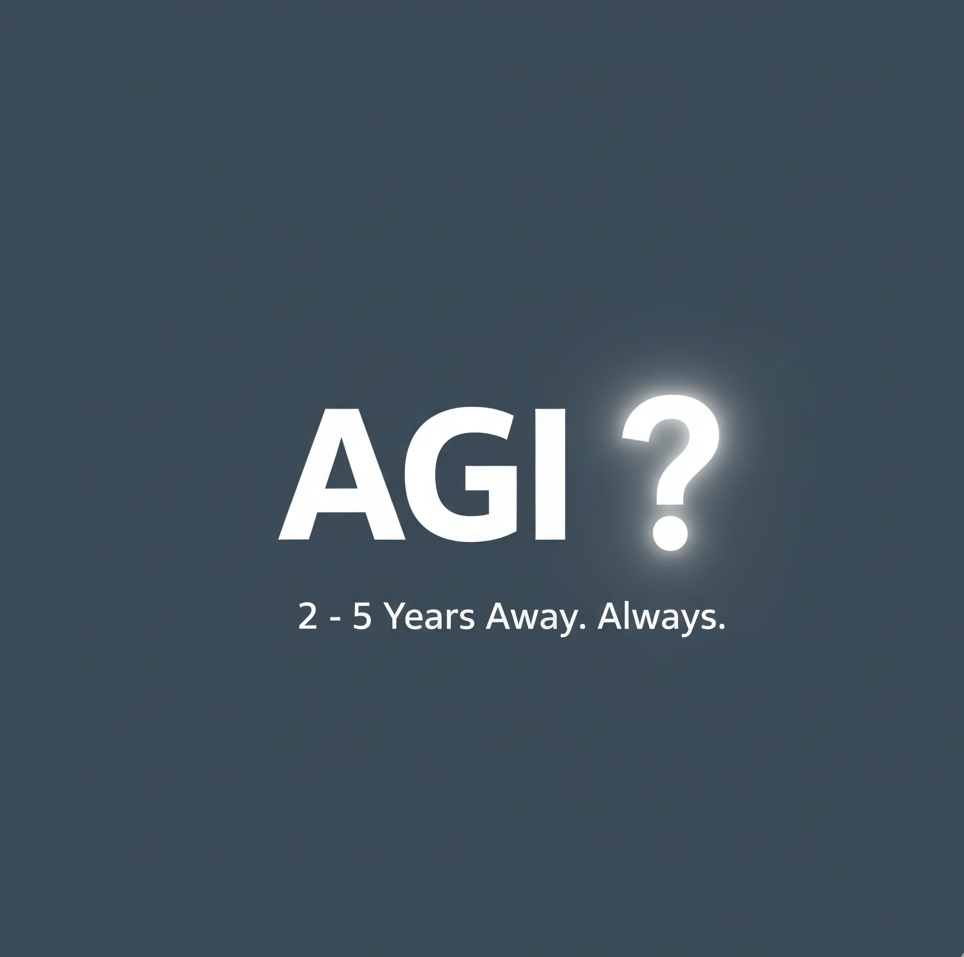

The reason for this shift is the "2-to-5-year" horizon. For decades, AGI has been perpetually just around the corner, close enough to justify massive speculative investment, but far enough away that its structural impossibilities remain untested. This "imminent" arrival creates a state of permanent emergency, where we are told to prepare for a digital god rather than to understand the limitations of a new hammer and learn to use it.

The discourse has become an unfalsifiable loop: whenever a model fails at basic reasoning or novelty, we’re told to 'just wait for the next version.' But what if the problem isn’t the scale of compute? It is the fundamental delusion that we can achieve 'intelligence' through computation and without even defining it, all while burning billions in the process.

The Shared Delusion: Both doomers and dreamers assume current technology leads to AGI. They’re both wrong

There's something deeply unnerving about the current AI discourse. Not the technology itself, but the conversation surrounding it, the unwarranted hype, the unnecessary fear, the massive misallocation of investment, the luminaries confidently declaring that jobs will soon vanish when history suggests otherwise.

These are tools, sophisticated ones certainly, but tools nonetheless. Excel didn't eliminate accountants, it empowered them, changed their work, made some tasks trivial and others possible. Yet we're told AI is fundamentally different, that this time the displacement is real, inevitable, imminent. Meanwhile, billions flow toward ventures premised on capabilities that are structurally impossible, and ordinary people oscillate between terror and messianic excitement.

What's frustrating is that the discourse suffers from a fundamental problem: almost everyone is having the wrong conversation.

Three Narratives, One Shared Delusion

Ordinary people oscillate between two extremes—either terrified by AI as an existential threat or excited as if living in a science fiction novel. Meanwhile, a large portion of programmers remain convinced that AGI is just a matter of more computing power or the next algorithmic breakthrough. These groups appear to disagree, but they share a common misconception: that we can achieve AGI within the current computational paradigm and technology.

The terrified think the current paradigm will produce AGI (and it scares them), the excited think it will produce AGI (and it thrills them), and the techno-optimists think it will produce AGI (they just need more resources). All assume the same impossible thing.

Then there are the rare dissenting voices, a few programmers, mathematicians, philosophers, who recognize the structural limitations of the computational approach. They point to problems like the creation of genuine novelty, the meaning problem, or the uncomfortable fact that we're racing to achieve "intelligence" without any coherent definition of what intelligence actually is. This should be alarming, yet these concerns remain largely unheard.

The Cascading Failure

This confusion doesn't stay contained in academic or technical circles. It cascades through society with real consequences:

Financial markets are pouring billions into ventures premised on AGI timelines that are fundamentally impossible, not just distant. The irony is that those few investors who understand the limitations can identify genuine value in narrow, well-defined applications where statistical pattern matching actually solves real problems. The hype obscures where the actual utility lies.

Politicians treat "AI" as a universal solution to complex social problems—healthcare, education, climate change—as if these domains were simply optimization problems awaiting sufficient compute. They're making policy decisions and societal investments based on the fantasy that because we have a sophisticated descendant of ELIZA, everything will be solved by AI. These decisions will have lasting consequences: misallocated resources, inappropriate automation, systems deployed where their fundamental limitations make them dangerous.

The general public is caught between terror and excitement, both narratives assuming capabilities that don't exist and will never be achievable through current approaches.

The Novelty Problem

Current AI systems are fundamentally interpolative. They recombine and transform what they've encountered in sophisticated ways, but they can only create novel arrangements of existing patterns. Intelligence involves more than recognizing and manipulating patterns, it requires the ability to create actual novelty, which means that currently we are optimizing toward something unreachable via computation alone.

The Meaning Problem

Even more fundamental is that these systems do not understand because they lack the capacity to develop meaning. They manipulate symbols according to statistical patterns without any grounding in what those symbols represent. A system can flawlessly translate between languages, answer complex questions, even write coherent essays, all while the words remain empty tokens in a computational process. Understanding requires meaning, no amount of pattern matching over text can substitute for this. We've built systems that can perform impressive linguistic behaviors while entirely bypassing the question of whether anything means anything to them at all. This isn't a gap that more data or better architectures will close, it's a category difference between processing information and actually understanding.

The Definitional Problem

Perhaps most troubling is that we're optimizing toward a target we cannot clearly specify. What do we even mean by intelligence? We have intuitions, demonstrations, benchmarks, but no coherent account of what we're actually trying to build. It's like navigating without knowing your destination, assuming you'll recognize it when you arrive.

The skeptical voices aren't simply saying "this won't work." They're pointing out something more unsettling: we don't know what "working" would even mean here, and the assumptions embedded in the computational approach may be hiding rather than solving the hard problems.

An Unfalsifiable Discourse

The conversation has become nearly impossible to correct. Admitting "this probably can't do X" is treated as evidence you don't understand the technology, when often it's the opposite. Any limitation demonstrated today can be dismissed with "just wait for the next model." The incentives—financial, professional, political—all point toward maintaining the fantasy.

Meanwhile, acknowledging limitations doesn't mean these systems are worthless. They're genuinely powerful tools for specific tasks. But we've created an environment where nuance is impossible.

Two Paths Forward

There are perhaps two ways this resolves:

The bubble bursts. The gap between promised capabilities and actual utility becomes undeniable when returns fail to materialize. But the damage done in the meantime, misallocated capital, careers built on false premises, flawed policy decisions, won't automatically reverse.

A new paradigm emerges that demonstrably goes beyond computation. But this raises uncomfortable questions: Would we even recognize it? Our entire framework for evaluating these systems is computational. A genuinely different paradigm might not be legible within our current ways of measuring and understanding.

The Cost of Fantasy

Until then, we're stuck with a discourse that fails everyone: investors chasing illusions, politicians making decisions based on capabilities that don't exist, and ordinary people unable to distinguish genuine capability from science fiction.

The tragedy is that honest conversation about both the power and limitations of these systems would serve everyone better. But honesty doesn't drive investment rounds, win elections, or generate headlines.

We're not living in a science fiction movie. We're living through a collective failure to grapple with what we've actually built, what it can and cannot do, and what we're really trying to achieve. Until we can have that conversation, until the incentives shift or reality intervenes, the madness continues.